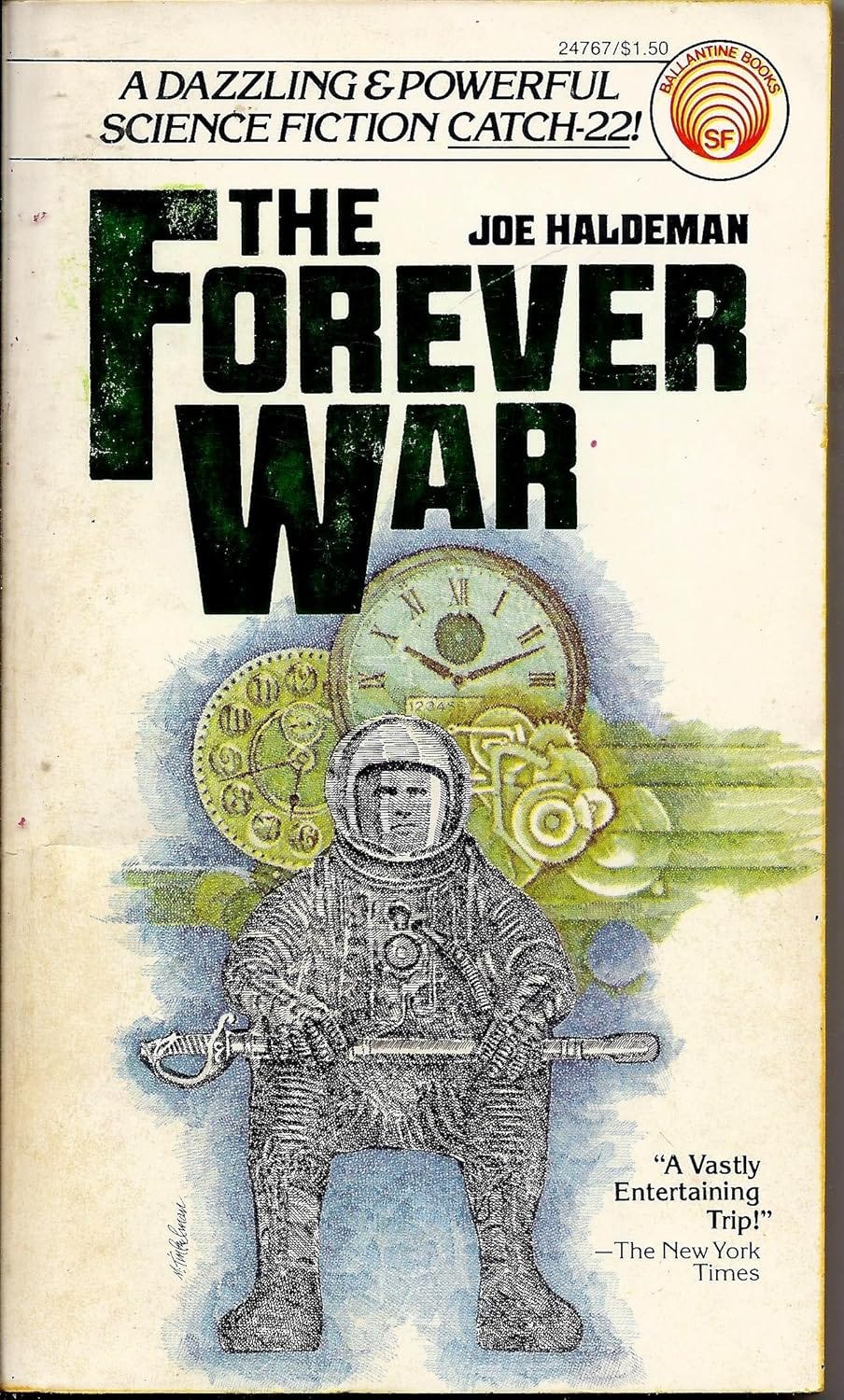

The label “Forever War” is frequently used to cast an on-going conflict in a bad light. It comes, of course, from the title of Joe Haldeman’s fantastic 1974 science fiction novel about a soldier fighting an interstellar war that seems to last forever because of the enormous distances involved and the relativistic effects of near-speed-of-light travel. That book was not about the Vietnam War, but it was not not about it, either. Haldeman was drafted in 1967; he served in Vietnam as a combat engineer in 1968 and received a Purple Heart. Acknowledging that it was his wartime experience that launched him on his writing career (he had intended to become a physicist), he famously wrote, “in my work, it always comes back to the jungle.” Anyway, the war in Haldeman’s book seems to be a pointless train wreck of galactic proportions, and today there appears to be a consensus that “forever wars” are bad. But are they?

Resistance to the idea of Forever Wars is grounded in the belief—which I share—that wars should be conducted in pursuit of clearly articulated and achievable policy goals. You identify a thing that needs to be done that can best be done through military force, you do that thing. You stop. You seize something. You compel an adversary to do something, or to stop doing something. That thing might take a long time to achieve, but the point is less the chronological duration than the presence or absence of a clearly defined goal. An end. Moreover, war must only be a means to an end, and never an end to itself. Sometimes wars that go on and on at least appear to do so because their perpetuation serves the political or even financial interests of some or all of the people responsible for perpetuating them. Is this always the case? Might a never-ending war be a good thing, or, more likely, a least-bad option?

The example of this being true that comes to mind first is the Afghanistan war. That war had no end in sight after almost two decades. Yet it also seemed to be the case that the United States could have kept it going seemingly forever at relatively low cost, and thereby prevented the Taliban from seizing power, or at least keep them out of Afghanistan’s major population centers. Most of the fighting in the war’s last years was being done by America’s Afghan allies; they could have kept it up indefinitely, provided the U.S. maintain a modicum of support. Had the U.S. done so, millions of Afghans today would be better off than they are now. Admittedly, the benefit to the United States is less clear. Some evoke the reputational damage done by abandoning an ally and capitulating to an enemy. Some point to the terrorist threat the Taliban, whose association with Al Qaeda is what led to the war in the first place, still represent. All this is debatable. The fact that it is debatable, however, underscores the point that keeping the war going might not have been the worst option. Indeed, while war is bad, so are the Taliban. Otherwise, why were we fighting them in the first place?

Presently, the United States is involved in a forever war in Somalia against the Islamist group known as Al-Shabaab. This war has been going on at least as far back as 2007, but really earlier, depending on how one understands earlier American counter-terror operations and their targets. Very rarely does anyone talk about this war, perhaps because the U.S. has managed to keep stirring the pot at relatively low cost in terms of lives and treasure. What’s interesting about it is that no one who does follow the war pretends it will end anytime soon, if ever. Somalia’s federal government lacks the strength to win, even with its international supporters, none of which are interested in increasing significantly the resources they are contributing to the fight. Al-Shabaab cannot win either, at least so long as the U.S. keep propping up the government and, from time to time, drone Al-Shabaab fighters or conduct raids against them. In other words, American policymakers, explicitly or implicitly, have concluded that keeping the war going at its current level is preferable to allowing Al-Shabaab to win, or making the kind of effort that might enable the Somali government to win.

I’d argue that “Forever Wars” are bad when they go on and on not because that is understood to be the best policy, but because their continuation stems from the failure of policy or the absence of policy. They are bad when they continue because one has lost one’s way and is adrift. It goes without saying that the perpetuation of a war for the sake of personal interest is monstrous. It is, however, hard to prove. Personal interests can be identified, but how does one know if they are the reason for any given policy choices or lack thereof?

If you like this work, please consider a paid subscription, or perhaps buying me a coffee by clicking here.

You should, of course, read Haldeman’s Forever Wars. This is an affiliate link meaning I get a tiny commission.

And do check out my YouTube channel.