Is Zionism Colonialism? Yes. And No.

Is it accurate, or even useful, to regard Zionism as colonialism, or Israel as a “settler colonial” state? It has long been a commonplace for Arab political and intellectual leaders along with Western activists to regard Zionists as colonialists, and to identify Palestinians as the quintessential colonized. More recently, it has become de rigeur in many circles to describe Israel as an “apartheid” state. I see this sort of rhetoric a lot in my professional work: I am a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center and have worked on Africa for almost two decades at RAND and the CIA. I teach a class at Syracuse University on African conflicts. All of this exposes me to a great deal of discussions about colonialism, anti-colonialism, etc. I also am unique among Africanists in that I have a Ph.D. in modern Jewish history; I began my career teaching Jewish history and, yes, Zionism, before my career took some unpredicted turns. Can Israel's sympathizers hold their noses and look such allegations in the face? And how can they be evaluated? This is what I seek to do answer here.

Arabs and the Ottomans began accusing Zionists of colonialism the moment the first Jewish pioneers arrived in Ottoman Palestine, with Ottoman authorities seeing it as yet another way for European powers to undermine the Empire and extend their power. Their claims took on form and vigor with the rise of Arab nationalism following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the dawn of the Mandate period, as Jewish colonialism became conflated with British Imperialism. Arab nationalism itself was if not born out of then at least nurtured by the anti-colonial struggle. The concomitant growth of Zionist Palestine (with limited and ambivalent British support) fueled the Arabs' fears that Zionism was an auxiliary of Western colonialism and guaranteed that anti-Zionism would be fundamental to Arab nationalism. It was in the 1950s, however, that anti-Zionism, inspired by the socialist and anti-colonial insurrections that swept the globe, acquired much of its present ideological content. The leaders of Arafat's generation looked at Israel and saw Indochina and, above all, Algeria. It was all the same fight for national liberation, one that could be won using the same basic methods: peasant guerilla war and urban terrorism. They have been fighting the same war ever since.

We can see all this clearly in a 1965 (before the Six Day War) publication by the Palestinian Liberation Organization entitled Zionist Colonialism in Palestine, written by Fayez Sayegh. Zionism, according to Sayegh, was a classic example of European settler-colonialism, and as such it was an anachronism in that Zionists founded their state just as liberation movements were rolling back European settler-colonialism elsewhere in the world. “The fading-out of a cruel and shameful period of world history has coincided with the emergence…of a new offshoot of European Imperialism and a new variety of racist Colonialism.” Sayegh traced Zionism’s roots to the “Scramble for Africa” of the 1880s. He stressed Zionism’s “vital and continuing association with European Imperialism,” and the alliance between Zionists and first British and then American Imperialism. Elsewhere he compared Israel with apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia, complaining—oddly—that Zionists were not satisfied with subjugating indigenous peoples to avail themselves of their labor (apartheid), but wanted instead to live entirely separately. For Sayegh, the solution to the Zionist problem was the same as for other anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggles:

“As a colonial venture, which anomalously came to bloom precisely when Colonialism was beginning to fade away, it is in fact a challenge to all anti-colonial peoples in Asia and Africa. For, in the final analysis, the cause of anti-colonialism and liberation is one and indivisible. (Emphasis in the original)”

The 1950s-1960s anti-colonial national liberation paradigm also was important because it seduced the Western Left (including a Jean-Paul Sartre and the incendiary Franz Fanon) to embrace national liberation movements as heroic causes in the name of which anything was justified, including terrorism. Soviet propaganda, determined to equate Zionism with racism—a key element of Sayegh’s argument—contributed. At that moment was born the Left's affinity for the Arab Palestinian cause, for it readily accepted the notion that the Palestinians’ struggle was that of a colonized people against chauvinist bourgeois nationalism and colonialism. Israel equals colonialism equals bourgeois capitalism, nationalism, and racism. Contemporary academic and intellectual anti-Zionism owes a great deal—especially its vocabulary—to the 1950s-1960s iteration.

Roger Water’s expression of the Israel = bourgeois capitalism = oppression equation.

This paradigm, as compelling as it may be, obscures some important differences between those fights and the fight with Israel. What are those differences? How can we evaluate in what ways Zionism is and is not colonialism or settler colonialism, a term that is in vogue these days?

What is Colonialism?

To answer this question, we must first ask a more basic one: what is colonialism? In search of a viable definition beyond the basic “establish a settlement somewhere else,” I turn to the best of the anti-colonial books written in the 1950s, Albert Memmi's 1957 double-essay Portrait du colonisé, précédé par Potrait du colonisateur (Portrait of the Colonized, preceded by Portrait of the Colonizer-- the current English edition bears the simpler title, The Colonizer and the Colonized). Several of Memmi's contemporaries wrote more daring or more intellectually sophisticated studies, most notably Fanon's Wretched of the Earth. However, Memmi's book offers certain clear advantages. One is his independence from the Marxist dogma and rhetoric that hobbled Fanon and Sartre. More important, however, is Memmi's own background, which gave him a uniquely objective perspective on colonialism: Albert Camus wrote of Memmi, "Here is a French writer from Tunisia who is neither French nor Tunisian..." "He is Jewish (with a Berber mother, which doesn't simplify anything) and a Tunisian subject [...] however he is not really Tunisian." In Memmi's own words he was "a native in a country of colonization, Jew in an anti-Semitic universe, and African in a world where Europe triumphed." He identified simultaneously with both colonized and colonizer while belonging to neither. While Memmi wanted us to understand the truth about colonialism, unlike Fanon, he had no interest in declaring war or calling for blood, for he was not about to make war on himself.

Memmi began his project because he had discovered that the "fact" of having been colonized affected most aspects of his life and personality, "not only my thinking, my own passions and my conduct, but also the conduct of others toward me." "I undertook this inventory of the condition of the Colonized," he wrote, "above all to understand myself and to identify my place among other men." From there came a recognition of the interdependency of colonizer and colonized and his insight that colonization created both. "The colonial relationship," he wrote, "chained the Colonizer and the Colonized in a type of relentless dependency, shaping their respective features and dictating their conduct." Memmi observed, for example, that the colonized becomes the colonized by accepting colonization and recognizing the colonizer. "It does not suffice for the colonized objectively to be a slave, he must recognize himself as such." He continued:

“... the colonizer must be recognized by the colonized. The link between the colonizer and the colonized is thus destructive and constructive. It destroys and recreates the two partners of colonization into colonizer and colonized: one is disfigured into an oppressor, a partial being, uncivil, cheating, uniquely preoccupied with his privileges and the defense of them at any cost; the other into an oppressed, broken in his development, accomplice to his own crushing.”

Neither colonizer nor colonized could exist without the other; the dialectic of their relationship defined both. It also doomed both. "Just as there was an evident logic to the reciprocal comportment of the two partners of colonization, another mechanism, that followed from the first, proceeded inexorably to the decomposition of that dependency."

Does Israel Fit Memmi’s Definition?

The parallels between Israel and the colonial relationship between colonizer and colonized described by Memmi are inescapable. One of the very first arguments Memmi makes, for instance, is that privilege is "at the heart of the colonial relationship," and that in colonialism the meanest colonizer is nonetheless more privileged than the richest colonized. This flies in the face of both liberal notions of meritocracy and Marxist models of class struggle, for it is birth (race) and not class that is the organizing principle of the colonial economic, legal, and social structures. Hence Sayegh’s repeated charge that Zionism is racist. Sadly, this kind of colonial privilege applies all too well to Israel—most obviously on the West Bank but inside Israel as well.

Memmi's arguments about the construction of the colonized appear to be similarly valid if only for the way they echo Zionist rhetoric about Arabs. According to Memmi, the colonizer constructs a "mythic" identity for the colonized through a series of libels and negations, and then he succeeds in imposing this identity on the colonized, who ends up by internalizing it, believing it, and living it to the point that the myth becomes reality. It is particularly noteworthy that Memmi identified laziness as the cornerstone of the colonizer's myth. How many times have I read or heard from Zionists about the failure of Arabs to develop natural resources, work the land, and improve their lot? Whether Palestinian Arabs have internalized these views, as Memmi suggested, I cannot judge.

Another effect of the colonizer on the colonized that seems particularly true for Israel is his argument about how colonization places the colonized "outside of history and outside of the community." "Colonization denies [the colonized] any part in war and in peace, in any decision that contributes to the destiny of the world or his own, any historic and social responsibility" Reading these words, I thought of a discussion I had in the 1990s with a friend in a West Bank settlement. As we stood at the edge of the settlement and looked out across the barren valley to an Arab village, I asked her what she wanted Arabs to do. Her answer was "nothing." Arabs should submit to Israeli authority, resign themselves to having been bested, put up passively with Jewish settlement, and do nothing. In other words, she would condemn Arabs to an existence with no stake in the future of the country in which they lived.

At the time I could sense the absurdity of my friend's position. It struck me that people can put up with being poor, but at the very least they must believe, however falsely, in the future. Memmi in fact explained such a situation leaves young Arabs with no avenue for evolution. They have no voice, no chance at power, no role to play in any of the decisions that might improve their lives. They have only one recourse. "The only way to evolve, really, is to rebel." Sayegh concurred.

Memmi offered warnings that appear to be directly relevant to Israel. The first is that the colonized in revolt cannot distinguish between 'innocent' and 'guilty' colonists. To them, all Europeans in the colony are colonists and thus colonizers. (One routinely hears the argument that all Israelis are fair targets for murder because they are all colonizers.) The second is that the rebels cannot be expected to emerge from the colonial experience as liberals and universalists. On the contrary, they will be chauvinists, nationalists, and very likely racists. For too long, Memmi explained, colonized people are told that they are different and that they cannot be assimilated. The colonized assimilates this idea and accepts it. "He will be that man" whom the colonizers have told him he is. "The same passion that made him admire and absorb Europe, will make him affirm his differences, for these differences, in the end, constitute him, constitute properly his essence." Memmi continued:

“[the colonized] will be nationalist and not, understandably, internationalist. Of course, this being the case, he risks slipping into exclusivism and chauvinism, to hold himself more upright, to oppose national solidarity to human solidarity, and even ethnic solidarity to national solidarity. But to expect the colonized, who has suffered so much from not existing for and by himself, to be open to the world, humanist and internationalist, appears to be comic foolishness.”

Memmi intended his remarks on the chauvinism of the colonized as a response to 1950s Leftists who were reluctant to embrace nascent colonial nationalisms because they were aggressive affirmations of particularist identity, whether ethnic, religious, or national, as opposed to universalist or, more ideally, proletarian. (Leftist Anti-Zionists today are reliably blind to Palestinian chauvinism; Zayegh himself seemed entirely blind to any notion that the racism of which he accuses Zionists might apply to Arabs.) Memmi was not endorsing the colonized's intolerance. As a Jew he suffered directly from Arab nationalism's inability to find a place for him in a post-colonial Tunisia, and the protagonist of his autobiographical novel Statue de Sel, after being rejected by his Arab nationalist friends, is forced to choose between emigrating to Palestine (Zionism) and emigrating to the New World. It says a lot that the Jewish protagonist of Arthur Schniztler’s beautiful 1908 novel Die Weg ins Freie, set in fin-de-siècle Vienna, finds himself in a similar dilemma as his non-Jewish friends turn to German nationalism and other rival ideologies, leaving him to flirt with Zionism.

A final area where Memmi's study fits Israel is his assessment of colonial politics. His disparagement of the colonialist Left makes for great reading, and its relevance to Israel's Left is intriguing. What I found more interesting, though, is his insight into the deformation of colonial politics in general relative to the metropole. Memmi observed that although colonists initially identify with the metropole, they eventually find themselves only supporting those aspects of the metropole that support them, in most cases reactionary and conservative elements. These the colonist regards as the 'true' nation. Threatening aspects, regarded as traitorous, are fought tooth and nail. Thus, the colonizer becomes a hyper-nationalist while at the same time developing a deep resentment of the metropole. He no longer has the same values as the metropole. To some extent, he is no longer a part of it. Worse, he threatens to poison the metropole with the "temptation of fascism."

These observations appear to apply directly to Israeli West Bank settlers, who often are rabid nationalists while at the same time nurturing a subversive resentment of the 'metropole,' in this case the largely-secular, non-triumphalist Israel on the other side of the Green Line. I have heard settlers say countless times that the government and mainstream Israelis "do not understand" or "have abandoned them." They feel personally threatened not just by liberal Israel but by the liberal democracy that frustrates their own agenda. This is why settlers and their supporters flirt dangerously with anti-liberal politics, and perhaps why Israeli’s current ruling coalition appears intent on “reforming” some aspects of Israel’s constitution that help protect the state’s liberalism. At least some pro-judicial reform Israelis couch their political cause in terms of preserving the “Jewish character” of the State. What they share is a sense of themselves as true Zionists who are upholding true Israel.

Memmi's portraits make clear that Zionism is colonialism at least to the extent that Israel reproduces between Jews and Arabs distinctly colonial relations that disfigure one party into colonizers and the other into colonized. However, his study should also make clear the limitations of applying archetypes to reality. If Zionism is colonialism in some ways, in others it does not fit the description. In fact, one can just as easily make the case that Zionism is a form of anti-colonialism, and in any case, there are important ways in which Israel does not fit the Algeria paradigm. The differences are not purely academic. They have great consequences particularly for those who seek to bring peace to the region. In particular, the comparison of Zionism with colonialism founders on three questions: Who are the colonizers? What is the metropole? What is the meaning of the word "occupation"?

Why Zionism is not colonialism

Memmi, in his subsequent Juifs et Arabs (Jews and Arabs), published in 1974, addresses the matter clearly:

“One does not find in the Israeli enterprise any of the characteristics of colonization in the contemporary sense: Neither the economic exploitation of an indigenous majority by a minority of colonists; nor the use of cheap labor, managed by colonizers who’ve reserved for themselves that role; nor the existence of a metropole, which is tied to the idea of a colonial exchange (raw materials for finished goods); nor a political and military power, directly or indirectly coming from the metropole; nor an alienation of agricultural lands to the sole benefit of the colonizers.”

One can take issue with the matter of the alienation of agricultural lands or use of cheap local labor, both of which are features of the Israeli economy. However, such things were never the purpose of the creation of the State of Israel. Zionism has never had an economic motive. In fact, many early Zionists wanted nothing to do with Arab labor because they hoped to create a Jewish proletariat, which they believed was necessary for a whole society, and which they also tied to the idea of regenerating Jews through labor. (Sayegh complained that this was worse than apartheid, and that it meant Zionism was about racial exclusivity.) The reality is that safety, not economic opportunity, is what drove most Jewish migration.

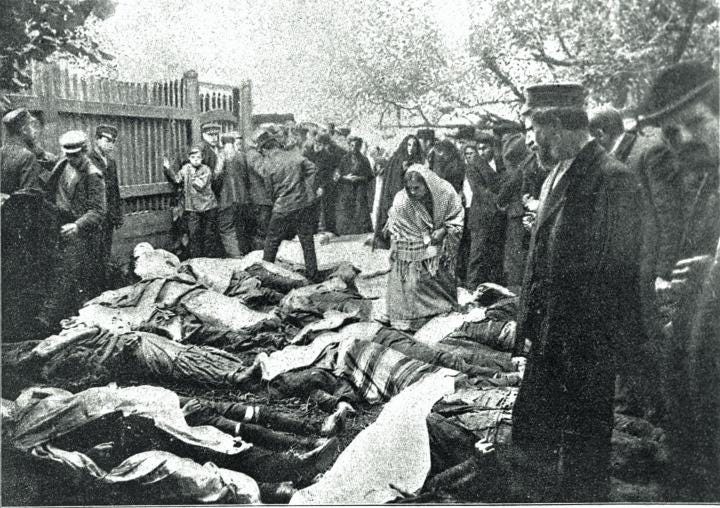

Pogrom victims, Bialystock, 1908.

Most Israelis are refugees or the direct descendants of refugees. This is part of what Memmi meant by insisting repeatedly on the need to recognize the “objective reality” of Jewish life in the diaspora (massacre, persecution) including in the Arab world. Sayegh made no reference to this; his review of the history of Israel and the Zionist movement shows no awareness of pre-World War II anti-Jewish violence worldwide or even of the Holocaust. Naturally, his depiction of pre-1948 violence in Palestine is laughably one-sided, as his brief description of the 1948 war itself. He made no mention of the persecution of Middle Eastern Jews in 1948 and after that spurred their mass emigration, often to Israel.

More important is Memmi’s argument about the absence of a metropole. The comparison of Israel with a colonial state implies the existence of a metropole, which in turn defines how people think about a “solution” to Israel, given that colonialism is seen as fundamentally wicked, a state of being that must be overturned. In the classic colonial model, France (or Britain, etc.) is the metropole, Algeria (or Tunisia, Morocco, Senegal, etc.) is the colony. Such clear-cut lines mean that the struggle against colonialism is equally well defined and limited in its objectives. The colonized fights to kick the colonizer back to the metropole; he has no brief against the metropole itself, does not aspire to destroy it, and could not do so if he wanted. And the metropole fights not for its own survival but for the survival of its colony.

The Israeli case, however, is not so straightforward. There is no metropole. If Israel is a colony, it is a colony of precisely whom? If Israel in expression of imperialism, it is part of what Empire? Without a metropole, there can be no "repatriation," for there never was a Jewish patria (except Israel, of course, or perhaps Judea, from whence the word “Jew” comes), and certainly no country that would welcome Jews back. Besides, roughly half of Israel’s population consists of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa, refugees from persecution, pogroms, and ethnic cleansing. Are they really expected to return home to Egypt, Iraq, and Syria, where they always were persecuted minorities and are guaranteed to be so once more, if not murdered upon their arrival? This is not a trivial point: people who insist that Israel is a colony at least imply that its inhabitants should go “home,” or away, whatever that means, or they dance around the issue by failing to address what precisely they imagine would happen if “Palestine” were to be “decolonized.”

Sayegh, writing in 1965, acknowledged that the Zionist project was unlike other European settler-colonial projects in that there was no Jewish metropole, and the Zionists’ goal was to build a nation in Palestine and use the settlement as a nation-building exercise. Key to his perspective was a denial of any Jewish connection to the land he mockingly refers to as “Eretz Israel” (always in quotes in his book), or the premise that Jews constituted a nation prior to the Zionist project. He was right that Zionists wanted to create a state; the Jewish nation however existed arguably since the Exodus, and for that matter in Europe at least non-Jews reinforced the idea by treating Jews as a separate nation living in their midst. Regardless, while he granted that the Zionist settler colony lacked a true metropole, nowhere in his text did he address the fundamental question of where Jews might go if Palestine were to be “decolonized.”

Many well-intentioned Westerners assume that Israel is the metropole and the territories seized in 1967 are the colony. They assume that when Arabs speak of "occupation," they mean the West Bank. It follows that the colonizers are the settlers in the West Bank. The fight for “Palestine” is thus about ending the occupation of the West Bank and sending the "colonists" back across the Green Line. Some Arabs think this way; it is what Arafat ostensibly agreed to when signing on to Oslo. This is a dangerous illusion. Arab critics of Zionism often speak of all Israel as an occupation, and all Israelis as occupiers and therefore colonizers and settlers. Of this Sayegh’s book, published in 1965, should leave no doubt. For them, the metropole to which Jews should return is a vague “West.” I’d go so far as to argue that the distinction between pre- and post-1967 borders is a fiction sold to willing Western liberals, who do not want to acknowledge that cries to “end the occupation” really mean ending Israel and the disappearance of its Jewish population, or at the very best its subjugation to a hostile power. That’s the meaning of “from the river to the sea.”

Zionism as a form of anti-colonialism and national liberation

A sympathetic reading of Jewish history reveals that Zionism, besides being motivated by the imperative of survival, is an anti-colonial ideology of national revolt. In fact, Jews can be considered the ultimate colonized people, with their colonization dating as far back as the Hellenist period and the Roman occupation of Judea. They have certainly exhibited all the traits of the colonized detailed by Memmi, including the assimilation of the values of the colonized and the pathology of defining oneself in relation to the colonizers’ ideals, to the point of self-hatred. (Memmi says as much, although when in Juifs et Arabs he declares Jews to be “colonized,” he refers specifically to the Jews of French North Africa.) Jews’ existence in the Diaspora was premised on their economic exploitation by sovereign powers, complimented by a legal and cultural system that placed them outside of history and outside the community. Jews were locked in the status quo. They correspondingly made a virtue of stability and quietism; their religion preserved them from despair and provided mechanisms for preserving a positive identity. Nonetheless, with the modern era many Jews hoped that by become more like those who dominated them, they might thrive and find safety. Even in tolerant lands like Revolutionary France, the offer of emancipation was conditional on at least agreeing to conformity, an offer that Jewish elites at the time accepted. They cannot be blamed for failing to anticipate that one day French police would round up their descendants and ship them off to Auschwitz.

Memmi himself saw Zionism as a form of national liberation and as much a part of the anti-colonial struggle as any other. A Zionist, he writes, is someone who, “having observed that the Jewish condition is one of oppression, finds it legitimate to reconstruct a Jewish State: To bring an end to that oppression, and to return to Jews, like other people, the dimensions of being free men.” Or, a Zionist is one who “believes in the desirability of the liberation of the Jew as such.” Memmi is adamant in his insistence on the recognition of Jews’ “objective” reality, i.e. persecution, and he stridently insists that European Jews did not have a monopoly on suffering. Arab Jews, he emphasizes again and again, knew only persecution, fear, and an abiding sense of fragility, and all this pre-dated the establishment of the State of Israel by centuries. “If one excepts the crematorium, the ensemble of victims of Russian, Polish, and Russian pogroms probably did not exceed those of the ensemble of successive little pogroms perpetuated in Arab lands.” For Memmi, the horrors associated with the “objective” Jewish “condition” must be considered, and they make a world of difference in trying to understand what Zionism and Israel are. “To consider,” he writes, “the Israeli adventure without reference to the threat and the oppression experienced by Jews throughout history and still today in the world, without reference to the global Jewish condition, is to wish to understand nothing.” By this standard, Sayegh understood nothing. Indeed, one simply cannot overlook the crisis experienced by Jews nearly everywhere in the world in the late 19th and early 20th century even before the Second World War, not to speak of the Holocaust and the liquidation of Jewish communities throughout the Arab world in the 1940s-1960s.

Jewish refugees from Yemen, 1950.

Zionists, like Memmi’s archetypal colonized, opted for revolt, couched in terms of national sovereignty and rebirth, which were commonplace in the empires of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In doing so, many Zionists also betrayed self-identities shaped by dynamics that resembled Memmi’s colonizer/colonized duo. Zionists like Theodore Herzl and Max Nordau looked contemptuously upon the average Jew. Indeed, Herzl and Nordau leave little doubt in their writing that they would happily assimilate if they could, if they thought Germans would have them. But they knew better. Anticipating Fanon by some sixty years, many Zionists envisioned regeneration through radical social and cultural revolution. Some hoped to transform themselves through agricultural labor. Others had vague notions of Nietzschean "transvaluation of values." A few looked to violence. The European Zionists at least (there were Zionists outside of Europe in Ottoman realms and elsewhere) drew from fin-de-siècle notions of honor, strength, and vitality. They wanted Jews to walk tall and to fight back. They wanted a Muskeljudentum. Like all colonized peoples, moreover, Zionists suffer from the syndrome of being trapped in a dialectical relationship with their colonizers, Europeans. "In full revolt," Memmi wrote, "the colonized continues to think, to feel, and to live against and thus in relation to the colonized and colonization." This meant, to a large degree, aping European norms, but doing so somewhere that the non-Jewish world would not turn on them.

When Arabs and the Left attack Zionism for chauvinism, nationalism, and racism, they are not entirely wrong. However, the chauvinism, nationalism, and racism of Zionism are those that, according to Memmi, should be expected of colonized peoples in revolt. Zionists are reacting to the hatred the world has dumped on Jews incessantly since the Romans destroyed Judea and forced its people into Exile. European Zionism, like Arab nationalism, is a fight against Europe, and the self-hatred that Jews absorbed there. It is as much an attempt by the colonized to regenerate themselves as that celebrated by Memmi and even Fanon and Sartre. Coming from European critics, the racism libel against Israel is cruel and ironic. Coming from Arabs, the accusation is little better.

The Apartheid Libel

The “apartheid” libel, a variant of the reductionist claim that Israel is a “settler-colonial” state, is particularly nefarious because it rhetorically associates Israel with apartheid-era South Africa and Rhodesia. These countries in contemporary liberal culture have become stand-ins for racism, which is now seen as one of the greatest of sins, making these countries quintessentially evil. Aside from the fact that modern Israel’s origins have little in common with South Africa and Rhodesia, whose white settlers were not refugees, had other places to go, and had no ties to the African continent whatsoever, what is implied by the comparison is wicked: Just as those countries (because evil) had to fall, and fall they did, to be replaced by majority rule, so, too must Israel. This is deemed inevitable and just. The ‘right’ side of history.

Proponents of this view might argue that it all turned out well for white South Africans. And who cares what happened to white Rhodesians, of which there were never many anyway? One imagines that a decolonized Palestine might become a “rainbow nation,” with Jews and Muslims living in harmony. Given the illiberalism of contemporary Palestinian society, the fact that Arabs and Muslims have nearly always persecuted Jews, that they have a miserable record of protecting religious minorities, and deny that Jewish holy sites have anything to do with Jews, it is absurd to think that a “decolonized” Palestine would be anything other than a scene of violence, massacres, persecution, and expulsions (to where? To what metropole?). Justice, it seems, would require that Jews in Israel return to a state of being colonized. It also is striking that while Israel is criticized for illiberalism, no one minds the fact that any successor Palestinian state is all but guaranteed to do no better.

Putting it together

Zionism and Israel ultimately have many features of colonialism. This relationship makes revolt all but necessary, and certainly understandable. At the same time, the label does not fit in several important ways. One might argue that not all features are necessary, and that having only some is bad enough. We insist, however, that not all colonialisms are the same, not all colonizers are equal, and the solution to one colonial context is not valid for all. Israel is not Algeria, and both Arabs and anyone interested in a peaceful solution must recognize where the similarities between the two cases stop. Israelis, unlike European colonists in most typical colonies, cannot "go home." Moreover, unlike the French, which never had any reason to be in Algeria in the first place (Charles X invaded in 1830 to distract public attention from his failed domestic policies), Jews had very urgent reasons to be in Israel—their only real homeland and the center of Jewish identity for millennia. Many will require a haven in the future. Any bid to “decolonize” all of Israel is not acceptable.

Even if Palestinians were to grant the legitimacy of pre-1967 Israel, we must accept that a scheme to decolonize West Bank and Gaza alone is so fraught with danger that Jews cannot reasonably be expected simply to walk away. Cries of “end the Occupation” are understandable, but it’s not that simple, even if we agree that ending the occupation of the West Bank is desirable. France, which never had anything more at stake than its pride, mustered the will to pull out of Algeria only after eight years of horrible war, hundreds of thousands of casualties, waves of fascist terrorism, and the collapse of the government. If France did not have De Gaulle to lead it, it may have fallen into civil war. All that for a colony that could not threaten France in any way, a colony that never brought France anything but trouble. In contrast, Israel has everything at stake. It has no sea to separate it from its seething neighbors, many of whom are plainly interested in taking the war to the metropole and destroying it. Israeli Jews have no reason to trust that "occupation" refers to Ramallah and not Haifa. And, despite having all the ingredients for a nasty civil war, Israel presently has no De Gaulle with the strength to overcome internal resistance and maintain national unity. Yitzhak Rabin came close. (De Gaulle, luckier, survived an assassination attempt by French hardliners over Algeria.)

Israel should 'decolonize' at least a large portion of West Bank, just as it has Gaza, because there, the structural dynamic Memmi associated with colonialism applies directly. Israel has no choice; Memmi made clear that the revolt will not end, and the status quo is unsustainable. The only way there will be peace, however, is if the Palestinians take to heart the notion that "occupation" refers to the West Bank and renounce schemes to “decolonize” all of Israel. This means no Palestinian Right of Return applied to pre-1967 Israel. This means exterminating rather than harboring Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and other maximalist parties, who have no interest in recognizing the 1948 borders and who successfully sabotaged Oslo. The Left and the media need to be honest about these groups and what they would do if they only had the power. At the same time, Israel must find the courage to pull back, retrench, and suppress its own extremists. Israelis must do everything in their power to sell to Palestinians the idea of co-existence. They must figure out how to enable Palestinians to escape from the colonizer/colonized dialectic, presumably by helping a nascent Palestinian state thrive. But it takes two sides to make it work.