For work reasons I’ve lately been having conversations with DC people about American responses to Venezuela President Nicolás Maduro’s threats to annex the Essequibo region of Guyana. One of the things I learned was that folks in Washington tend to think the threat was not credible. In the process, they reminded me once again of how often DC establishment people seem to lack imagination when it comes to what potential adversaries might do, sometimes with terrible results.

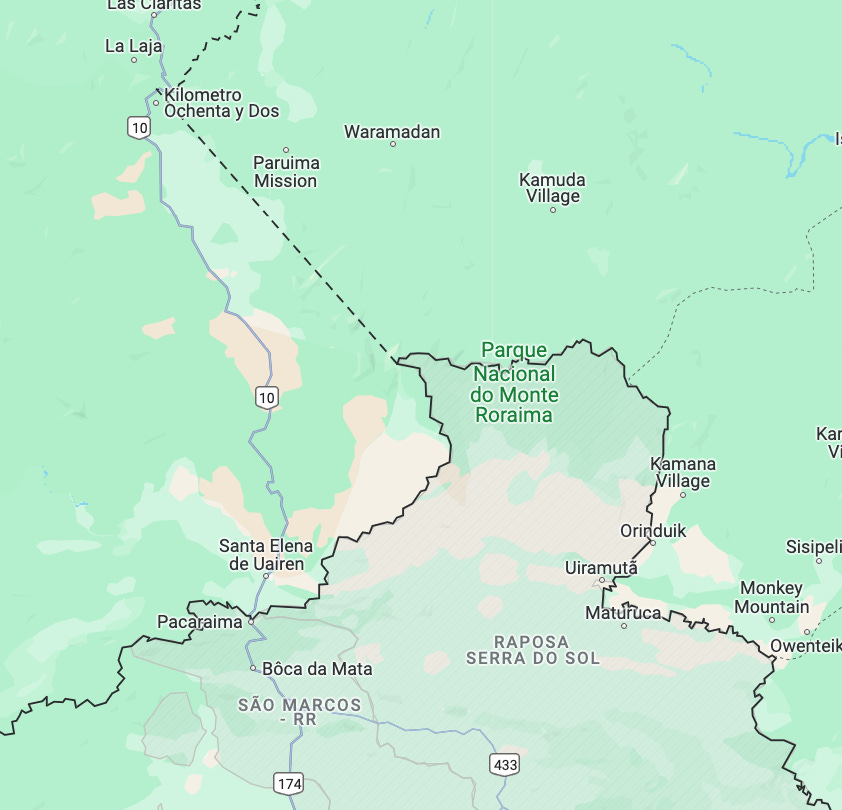

Territory claimed by Venezuela, west of the Essequibo River

The argument I heard was as follows: Venezuela was unlikely to attack Guyana, a country with no real military to speak of, because the Essequibo region is extremely difficult to invade due to its dense forests, mountains, and waterways. The only real road, I was told, goes through Brazil, and Brazil surely would not permit an invading Venezuelan army to pass through its territory.

To invade Essquibo, people say, one has to drive south on 10 into Brazil before being able to turn east into Guyana.

Thus, Washington Post columnist Charles Lane confidently affirms:

What’s more, even the world’s most capable militaries would blanch at trying to conquer the Essequibo region, a remote, heavily forested area comprising two-thirds of Guyana’s 83,000 square miles. The task is far beyond the scope of Venezuela’s corrupt Bolivarian National Armed Forces. This reminds me of a lot of things. Like when everyone believed somehow that Germany could never invade France through the Ardennes forest, which would allow Hitler’s Panzer divisions to go around the Maginot Line. (He did precisely that.) Or when Israelis assumed it would take Egyptian sappers days to breach the sand berms on the Suez Canal. (It took the Egyptians only a couple of hours, because they figured out a way to ‘melt’ the berms using high-pressure water pumps). Or when American policymakers discounted the idea that Saddam Hussein might attack Kuwait. No one ever believed jihadist terrorists would fly planes into skyscrapers (never mind the fact that an Algerian Jihadist group in 1994 planned to fly a plane into the Eiffel Tower before being foiled by French special forces who stormed the hijacked plane and killed the hijackers). Who believed Putin would launch an invasion of Ukraine in 2022?

The reality is that actors like Maduro might not be rational. Or, they are rational but come to different conclusions than we do, for one reason or another. The risk calculus of political leaders might include factors and variables different from what outsiders assume them to be. Perhaps Maduro holds his armed forces in higher esteem then is merited, the way Saddam Hussein seemed to think his armies could take on the United States? Maduro has plenty of good reasons to try: Venezuelan nationalists of the sort who back his regime staunchly support grabbing Essequibo, and Maduro, hungry for popular support, may believe that throwing raw meat at the very nationalists he’s been whipping into a frenzy as part of his “anti-imperialist” crusade is a marvelously clever thing to do. A move against Guyana would be very popular among many Venezuelans. It also would be an effective distraction from the country’s profound economic difficulties, not to mention the salutary effect Guyanese oil would have for those difficulties.

There’s more: Why does anything think Venezuela has to invade Essequibo, as if that was the only way for Maduro to force Guyana to cede territory to him? The proven oil reserves, by the way, are in fact off Guyana’s coast. There may be oil in Essequibo region itself, perhaps lots of it, but that’s not what Exxon and others are rushing to produce.

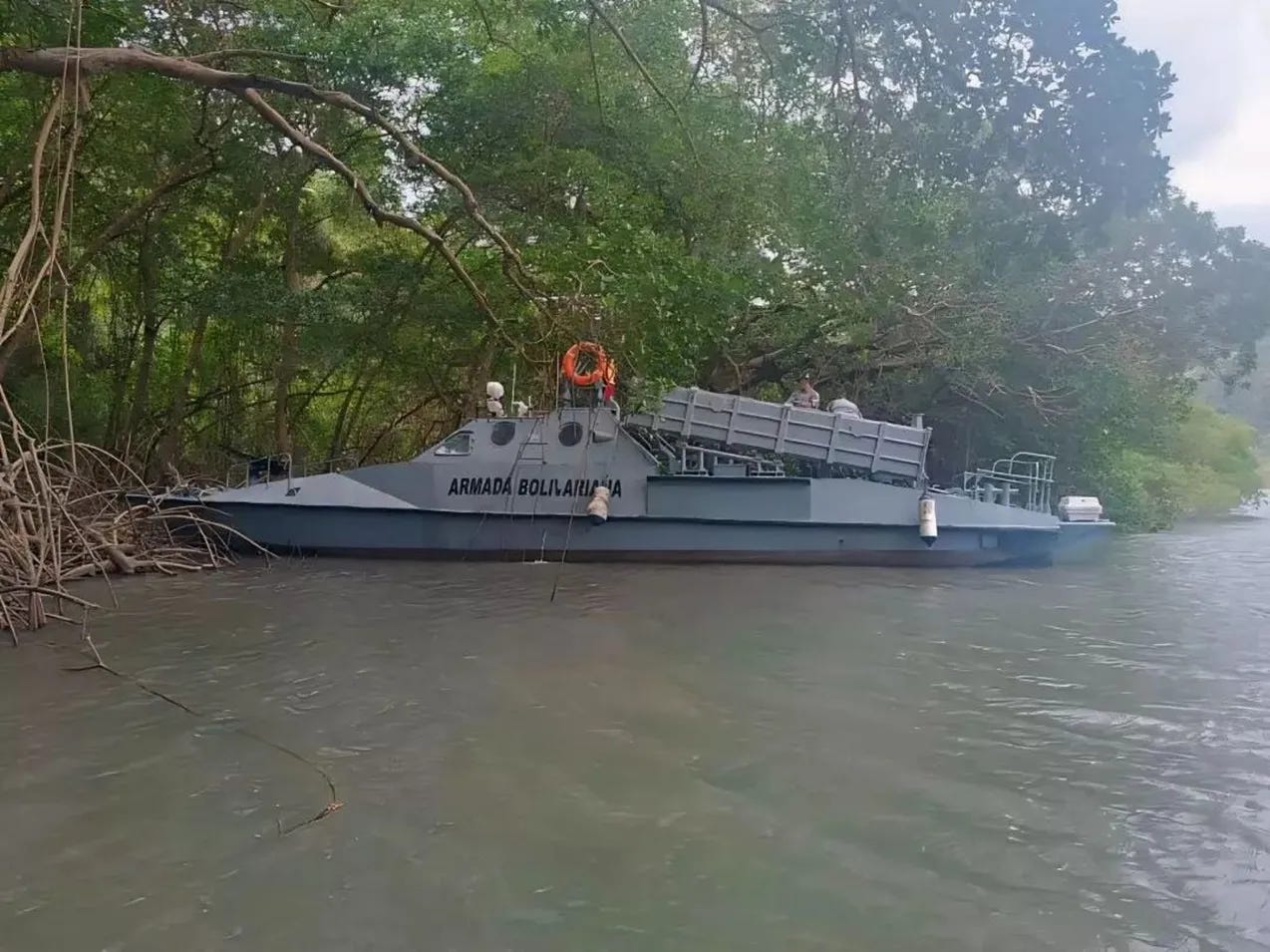

Iran in the past decade has been furnishing Venezuela’s armed forces with a modern arsenal of dangerous weapons that give Maduro multiple ways to inflict serious pain on Guyana and the entire region. These weapons included missiles, military drones, and small but potent warships—torpedo boats, really—armed with guided torpedoes and anti-ship cruise missiles.

Iranian Torpedo Boat Armed with Missiles, Venezuelan Navy

These give Venezuela the ability to wreak havoc on Guyana’s ports and deep inland via its rivers. It could wreck off-shore Guyanese oil wells, or simply scare off the oil companies now working to tap Guyana’s off-shore oil wealth, with disastrous consequences for Guyana’s economy, buoyed as it currently is by the oil rush. Maduro could disrupt commercial traffic in the Caribbean. Would he? Who knows? But Venezuela could. Moreover, whereas something as over-the-top as a big land invasion might incur the wrath of Brazil or the United States, it is plausible that something more limited, like acting in ways that scare off Exxon, might fall below the threshold that would trigger a big Brazilian or American response. Or so Maduro might think. Basically, Maduro’s ability to harm Guyana is limited only by his imagination.

I do not intend here to make predictions regarding whether Maduro will attack Guyana. Maybe he will, maybe he won’t. I have no idea. My point really is to question the apparent consensus in Washington, DC that he won’t and can’t. Indeed, part of the argument why he won’t is the assumption that he can’t. The thing is, he can. And, indeed, he just might.

The Trump Administration saw Maduro not just as a threat but as an American node of a dark network the epicenter of which really is in Damascus or Tehran. This is not entirely crazy. Its response was a “maximum pressure” campaign consisting of stiff economic sanctions. Empirically speaking, it is not clear that the campaign accomplished anything other than contribute to Venezuela’s economic decline, which arguably has weakened Maduro. Maybe. Biden’s approach, predictably, has been much more conciliatory. In 2023 Maduro signed the Barbados Agreement in which he promised to take certain steps thought to help ensure that the Venezuelan elections approximate “free and fair.” Immediately after, the Biden Administration rewarded Maduro by relaxing the Trump-era sanctions regime and implicitly threatening to restore them in full if Maduro does not abide by the Agreement. The Administration is keen not to provide Maduro a pretext for violating the Agreement. Of course, he already has, according to many reports. Maduro is testing to see what he can get away with. This is predictable, except perhaps in State Department land.

Which way is the better way? That is a difficult question, given the debatable efficacy of “maximum pressure,” which also does not appear to have born any fruit when applied to Iran. Is there a third way?

For a fascinating study of Israel’s Bar Lev line and how Israel’s assumptions about its impenetrability nearly proved fatal, see here: https://amzn.to/3VKetUs