People often speak of “rational actors” in international relations. The idea is that we usually can presume foreign leaders and governments to be rational, or at least not insane. This outlook is crucial for deterrence, especially nuclear deterrence. The whole idea of deterrence is that one can deter someone from doing something by guaranteeing that if they persisted, they would pay a price greater than the value of doing that thing. This presumes, of course, that the person one hopes to deter can weigh risk rationally against expected benefit and come to a conclusion we would expect of a reasonable person. We can reasonably expect Russian leaders, for example, not to wish to destroy the world and thus risk something that might result in a nuclear exchange. So far, that assumption has been correct.

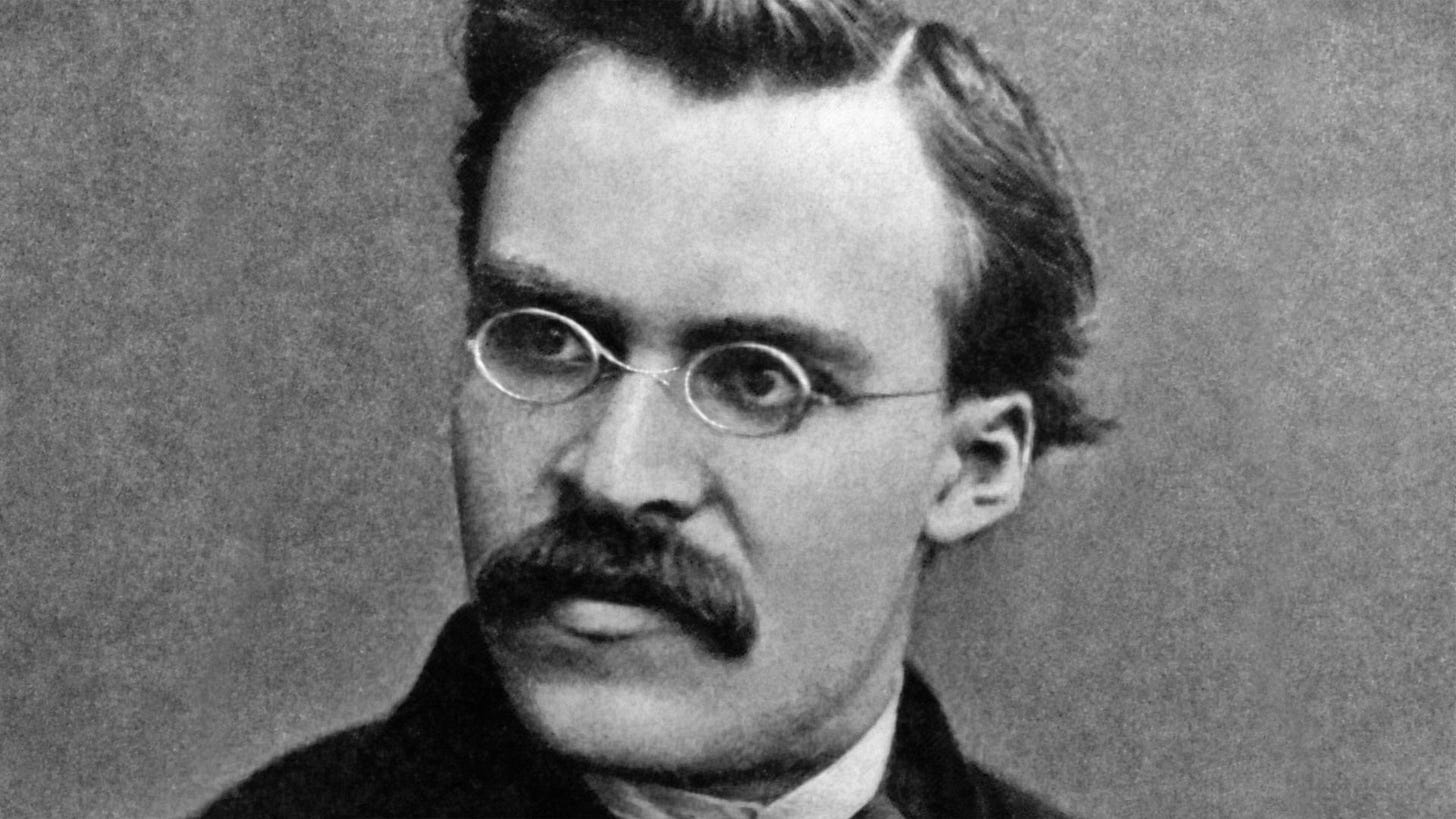

Nietzsche. Barking mad…or was he?

A problem with the rational actor theory is that there are plenty of examples of leaders and people doing things contrary to what we would expect “reasonable” people to do. They might, for example, act against their own self-interest. They might act out of passion. Or spite. Besides, “rational” often is in the eye of the beholder. What might seem rational to someone might appear crazy to another.

I believe an under-appreciated driver of international relations is ressentiment. I use the French spelling of the perfectly correct English word, resentment, not out of my usual Francophilia but to tie what I have in mind to Friederich Nietzsche, who used the French word rather than any German equivalents because he found them lacking. All the English translations of Nietzsche I have read (my German is not good enough to tackle Nietzsche) all insist on using the French word.

For Nietzsche, the concept of ressentiment is the key to his theory about the development of morality and the concept of evil. Basically, the inferior or the subordinate, rather than accept its inferiority or subordination, which it detests but is powerless to alter, learns to see its superior as bad, or even evil, while it classifies itself as good. Ressentiment is a psychological state that arises from suppressed feelings of envy, impotence, and inferiority, and which one redirects outward as hostility or moral condemnation toward others. One attributes one’s suffering and sense of inferiority to external causes or scapegoats, rather than confronting one’s own limitations. This leads to a worldview where one blames others and condemns them as the sources of one’s own pain.

Nietzsche famously tied the idea of ressentiment to his concept of the “slave revolt in morality.” The powerless (slaves) cannot compete with the powerful (masters) on their terms, so they redefine values: What was once considered good (strength, nobility) is recast as evil, and the opposite traits (humility, compassion, and weakness) are elevated as “good.” Ressentiment is not passive: One desires revenge. One wishes to see the supposed wrongdoers punished or brought low. Ressentiment is, moreover, a sentiment that simmers. It expresses itself through moralizing, scheming, and the creation of value systems that justify one's own weakness and condemn the strengths of others. In essence, Nietzsche sees ressentiment as a psychological process by which the weak, unable to act directly, invent moral systems that turn their powerlessness into a supposed virtue and condemn the powerful as evil

Nietzsche’s oft-cited example is the metaphor of “lambs” and “birds of prey.” The lambs, incapable of defending themselves against the birds, define the birds as “evil” and themselves as “good.” What matters for Nietzsche is that this is not an objective moral judgement but an expression of powerlessness that drives a need to redefine values. I would suggest another example, that of a man frustrated by his inability to bed women who labels women who sleep with other men “sluts,” and blames his failings on their behavior and perhaps that of the men who are more successful than he. He makes a moral judgement against them while recasting his own celibacy in terms of virtue. Perhaps this explains the so-called “incel.”

Central to Nietzsche’s concept of the “slave revolt” is the role played by the “priest,” which he contrasts with noble aristocrats. Whereas aristocrats create values from a position of strength and affirmation, priests develop their values reactively, in opposition to the values of the aristocrats. Lacking physical power, the priests act on their ressentiment by inverting the nobles’ value system. What the nobles call good (strength, power), they redefine as “evil,” while they define qualities born of weakness (humility, suffering) as “good.” This Nietzsche describes as the “transvaluation of values.” The priest accomplishes this through subversion and manipulation. They preach virtues that justify their own condition and appeal to the masses of the weak and disenfranchised, those gaining power over the weak, and eventually the strong.

Turning to international relations, more than a few countries, rather than being rational actors, are better described as being animated by Nietzschean ressentiment. Being or having been weak, they go well beyond aspiring to acquire power and rebalance their relations with formerly dominant powers. They go beyond holding a grudge. They justify themselves by casting others as the source of their weakness and misery, while elevating themselves in their own eyes. Others are not just bad. They are evil. They are worthy of hatred. The irony is that in doing so, they cultivate what essentially are negative identities that depend on the existence of another rather than positive identities that stand on their own.

Two examples that come immediately to mind are Iran and Turkey. Both suffered centuries of humiliating degradation by Western powers that take advantage of their relative weakness to exploit them. On the Turkish side, this is not something I understood until I visited the Ataturk Mausoleum in Ankara, where I was exposed to Turkish narratives about the origins of modern Turkey. Basically, in Turkish eyes, the Western powers gangraped Turkey at the end of the First World War and in the years immediately following. This came, of course, after a century of humiliations wrought by the capitulation system, whereby European powers ate away at Ottoman sovereignty and undermined its economy.

Iran, similarly, suffered from decades of predatory European intervention before finding itself occupied during World War Two and subject to further Great Power machinations afterward. Like the Turks, they blamed the West for their low station in the world, their powerlessness and their poverty. But more importantly, like the Turks, the Iranians channeled their ressentiment into poisonous ideologies that pair nationalist zeal with religious dogma. No one incarnates Nietzsche’s priest better than modern Iran’s Ayatollahs.

And then there are the Houthis. I know not what their “problem” is, but they seem to have seized upon hatred in proportion to their wretchedness. When I see them and the Iranians flinging missiles and drones at people they are determined to hate, I can’t help but think of Caliban’s retort in The Tempest upon being taught language.

You taught me language, and my profit on ’t

Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you

For learning me your language!

They have learned science and engineering (at least the Iranians), certainly. But their only profit on it is that they know how to weaponize it, and cast it at their enemies to kill.

Ressentiment makes one question deterrence. How does one deter someone animated by ressentiment? In a way, applying superior military pressure only validates their ideology and value system. Hamas, the Houthis, and perhaps the Iranians value martyrdom over the well-being of their people; they see virtue in suffering. They’d rather suffer their children being killed by Israeli bombs than release hostages. So how does one deter them? What price might be so great that they might be deterred from an action?