Syria’s government has fallen, to the astonishment of all observers who, until a little over a week ago, saw no end in sight to the horrible civil war there. Then something happened. I am not sure anyone yet has pieced together the sequence of events, but it seems clear that the difference between now and anytime in the past since the Syrian civil war began in 2011 is that Israel greatly weakened Iran and its chief proxy, Hezbollah, whose support for Syria turns out to have been critical. One can go so far as to conclude that had 7 October never happened, Assad’s regime would not have fallen, or at least not this year. To this we must add the fact that the Ukraine war appears to have badly weakened the regime’s other main source of support, Russia.

So what now? And what role if any should the United States play?

What happens now is that the main leaders of the rebellion have to organize themselves and work out some sort of deal for replacing the regime with some new political dispensation that they can all accept. I admit to not knowing enough about these groups to assess the probability of their pulling off such a difficult task. Historically speaking, it can be done, but it won’t be easy, especially since so many of these groups have competing agendas that do not lend themselves to negotiated settlements. There will be winners and losers; who’s to say if the losers will be content, and what they might choose to do about it?

Perhaps the biggest potential spoiler will be Turkey, which is squarely behind the so-called Syrian National Army and the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham , or HTS. The HTS, by the way, has emerged as the most powerful and influential of Syria’s rebel groups, but it also is among the groups that outsiders worry about the most. It is a jihadist organization that the United States has designated as a terrorist group. Washington placed a $10 million bounty on the head of the HTS leader, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani. Jolani spent a lot of time in Iraq, where he fought for Al Qaeda, and is considered a founding father of Islamic State (IS). In recent years he has been trying to distance himself from Al Qaeda and IS and obtain international legitimacy. No one really knows how sincere he is about any of this.

Syrian rebel leader Jolani. Jihadist or Peacemaker?

Turkey has a soft spot for Islamism, which already is a problem. But Turkey also is hostile to Kurdish autonomy, and the Kurds undoubtedly hope to win at least a measure of autonomy in a future Syria. Moreover, the main international backer of Syria’s Kurds is the United States, which puts Washington on a collision course with Ankara. To some degree, therefore, the U.S. may be in a position to restrain Turkish ambition, which might be necessary for achieving a political compromise among Syria’s new rulers. But can the United States? Or, perhaps more relevantly, will the United States?

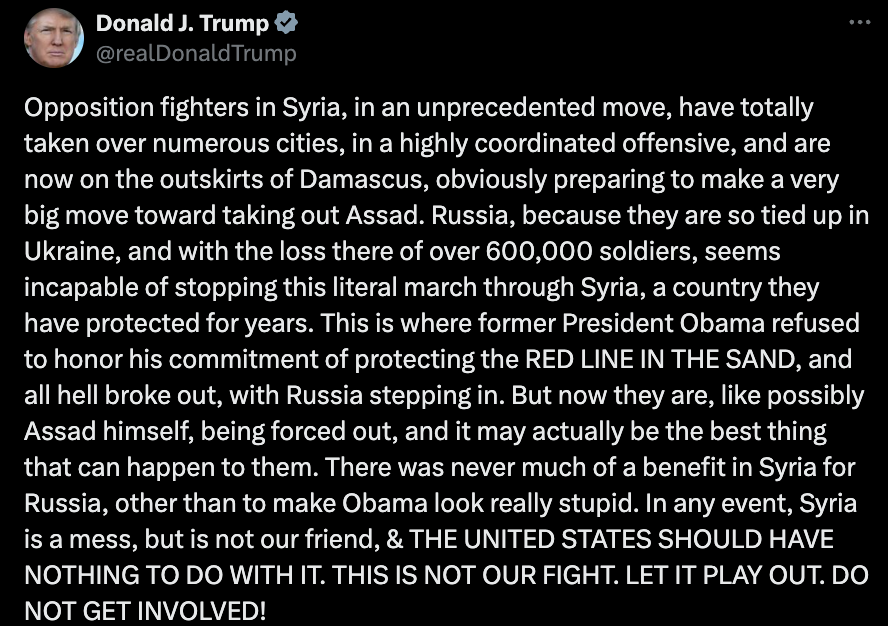

America has been involved in Syria since the beginning of the war, most of the time working with the Kurds primarily for the purpose of combatting Islamic State. However, Washington consistently has acted haltingly and hesitatingly. One reason is a lack of clarity regarding American objectives beyond fighting IS. Another is ambivalence about who it would like to see take the reins in Syria. Finally, it has been reticent to deal firmly with Turkey. Trump during his first administration tried to pull U.S. forces out of Syria but effectively was talked out of it. Biden, while committed to keeping U.S. forces in Syria, nonetheless has allowed path dependency to dictate U.S. policy, meaning the White House never budged from the hesitant half-measures of Obama and Trump. As for the second Trump administration, Trump himself gave a good indication of his view in the following Tweet:

The key bit is what comes at the end, “THE UNITED STATES SHOULD HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH IT. THIS IS NOT OUR FIGHT. LET IT PLAY OUT. DO NOT GET INVOLVED!”

That suggests that either he’ll withdraw U.S. forces, or they’ll stay on and keep doing what they’ve been doing, which is providing some help to Kurdish groups while focusing in IS, which never really went away. Is that enough to influence developments in Syria? Is that enough to restrain Turkey? Probably not.

This matters because absent U.S. resolve, Turkey will be the major player. That perhaps will not be a bad thing for most Syrians, if Turkey uses its influence to help fashion a stable political dispensation. It almost certainly will be bad for Kurds, who once again will find themselves history’s tragic losers. Europe in theory could help; it certainly has an interest in trying to stabilize Syria if for no other reason than to stem the flow of Syrian refugees and ideally reverse it. Regrettably, Europeans, France included, appear to lack the stomach for anything more than strongly worded statements.

Israel might help; it has good ties with Kurds, and deteriorating relations with Turkey might encourage Israel to collaborate more substantially with Kurds than has been the case previously. Still, it strikes me as implausible that Israel will risk confronting Turkey in that way. Turkey is far more powerful than Iran. It also, thankfully, has proven to be far less hostile toward Iran, even in recent years, but that could change. Jerusalem should think twice about adding fuel to that particular fire.

Speaking of Israel, its recent land-grab of Mt. Hermon and the slip of land located in what amounts to a Demilitarized Zone on the border between it and Syria is puzzling. Mt. Hermon is a real plum given its value for being able to look into Lebanon and Syria and watch events—not to mention incoming drones. As for the new so-called buffer zone on the DMZ, it is not clear if Israel perceives real threats on the border or is anticipating them. Much might depend on whether Syria’s Druze communities who reportedly dominate that part of Syria intend to assert autonomy and control over the territory, or work with whatever emerges in Damascus. Or, perhaps they want autonomy but lack the strength to affirm it? This matters because the Druze themselves are not a threat to Israel; the threat comes from jihadist Muslims of either the Sunni (Al Qaeda, HTS, or Islamic State) variety, or the Shia (Hezbollah). Druze are not Muslims. Might Israel back a Syrian Druze bid to control the area and assert their autonomy? Would the Druze even want that? Maybe. Grabbing the buffer zone suggests that Israeli leaders assume the Druze cannot or will not.

Israeli troops on the Syrian side of Mt. Hermon, to which Israel just helped itself.

This could all work out well for all concerned, the Syrian people above all, but also Israel and Lebanon. All it really requires is for pragmatism to rule the day, as well as a spirit of compromise. Turkish self-restraint would help. America staying involved also would help. Frankly, though, I’m not optimistic. That said, the horrors now being revealed in Bashar al-Assad’s prisons make clear that the regime of Bashar al-Assad had to go, regardless of the risk the future entails. Dude was evil.